Aldus Manutius: publisher of the European Renaissance

- Europe tends to forget the extraordinary technological developments and inventions which characterised its past.

- In the Renaissance, Aldus Manutius was the first modern publisher who made the book an easily available resource for the European peoples

- Describing the wonderful habits of the Utopia island, Thomas More said that its inhabitants made use only of Aldine editions

This technology, which is mostly developed outside of the Union, fails to foster an enthusiasm for innovation among EU citizens. Rather, it tends to disorientate people. They fail to recognise that the reasons behind the extraordinary technological developments that have hitherto characterised Europe derive precisely from its ability to review its past critically, and draw inspiration from this for self-improvement. In this context, any attempt to place its remaining hopes of recovery on the stratagems of financial engineering will fail to recreate that covenant between citizens and institutions. A covenant that is essential to restore the confidence that has inspired the most significant features of European history. Our reflection on the importance of ruling over innovation starts from a specific historical event. This year marks the fifth centenary of the death of Aldus Manutius, the most important publisher of the Renaissance.

Aldus Manutius (Aldo Manuzio)

He died in Venice, 6th February 1515, at the end of a life that saw him play a key part in the most significant transformation in communication of his time – a transformation that went on to inform the arts and sciences in Europe for centuries.

Manutius was born around the middle of the fifteenth century in the vicinity of Rome. He spent the first part of his life studying and teaching Latin and Greek at a time when – in part because of the trauma caused by the recent fall of Constantinople at the hands of the Ottoman Empire – an interest in Classical languages and culture induced a renewed confidence in the intellectual abilities of mankind.

The loss of this former Byzantine Empire capital resulted in a fear of the subsequent disappearance of its libraries, books, and knowledge.

This anxiety fueled, on the one hand, a fear of losing the intellectual foundations of its culture, and, on the other, a desire to protect these traditional roots by putting into field the new writing technologies that were spreading in the meantime.

Therefore, to study Greek was to recover and resume its philosophy and science from the original texts. Rediscovered from the corrupted medieval apocrypha, these purified texts were given new life.

It was not merely a matter of protecting an illustrious past as an end in and of itself. Instead, by returning to and rereading those seminal documents, it was a matter of looking beyond, toward a better, unknown future.

Around 1490, the temperate teacher of Greek – now older and in the service of the little princes of the Po valley – arrived, rather unexpectedly, at a turning point in his life. He moved to Venice, a place that, in his words, seemed more than just a city: it was “an entire world”.

During that time the Venetian publishing industry witnessed an impressive growth, thanks to the legions of printers that moved to the city from Northern Europe. Manutius, too, entered into the publishing profession.

He realised that as a publisher he could devote himself to the dissemination of Greek language and philosophy far more effectively than he could through individual interactions with students.

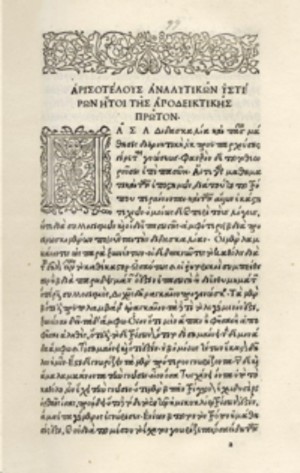

The Aristoteles of Aldus Manutius, 1495-98

(Libreria Antiquaria Pregliasco, Turin)

For about twenty years, starting from 1494, Manutius played a key role in the communication and technological revolution that dominated the Renaissance and had a lasting and profound effect on Europe, even to this day.

He transformed the printed book into the most effective tool for the accumulation and dissemination of human knowledge of the last five centuries.

While Gutenberg invented movable type fifty years before, making mass printing an engineering possibility, it was Manutius who made the book an easily available resource for the European peoples.

As is often the case, the individual who dedicates himself to the technical aspects of a project rarely possesses the necessary vision to imagine the impact and consequences of his own invention.

During those years of constant military threat and bloody warfare across Europe and the Mediterranean, the book, for Manutius, represented a lifeline.

It was capable of uniting an ideal republic, brought together across the continent through their love of letters. It was to these men of letters and science that he addressed his work. In the prefaces to his editions he makes incessant reference to the suffering caused by wars and political crises.

To contrast this, he advocates the humanistic belief that books and education are an essential resource for humanity, with his own words acting as evidence for this. Only the “good books” he writes “sweep away once and for all the barbarity.”

“Only they,” he adds in 1504 in the preface to the orations of Demosthenes, “could represent a lesson of hope against the tyrants, teaching those who read them to be worthy for their community.”

Manutius was the first modern publisher, taking charge both of a book’s content (what should be printed) and its form (its typographical aspects), fine-tuning every detail.

On the one hand, he approached the book according to a precise and coherent cultural program, which worked both to recover eminent Greek thought and to develop the linguistic tools necessary to understand this.

He was the individual who defined the philosophical and scientific canon on which the education of the Europeans was to be based, beginning with Aristotle and Plato.

On the other hand, and as an immediate consequence of this first aim, he approached the book as an instrument and object.

Manutius understood the full potential of the press and invented those devices that have made the book what it has essentially remained up to now – something for which we must give him credit.

He devoted his attention to the design of typographical characters, perfecting those already extant and inventing new ones, like italics. He devised systems that allowed easy orientation within the text, such as page numbering and indexes, and developed ways to made reading easier, like new punctuation signs and smaller formats.

Through these multiple small but significant formal and typographical changes he created, together with a disengaged reading, new readers and new cultural habits.

We cannot emphasise enough the revolutionary consequences of the adoption of the “octavo” format, which placed books outside of the studio environment and fueled the diffusion of reading among women and men who did not consider learning their exclusive or predominant activity.

While it may be anachronistic to suggest that Manutius considered the ‘mass market’ as we understand it now, there is no doubt that he paved the way for this way of thinking. His work made it possible to overcome the prejudices that still surrounded the printed book.

The mass market came later, yes, but the 3,000 copies of his paperback editions – which were immediately counterfeited around Europe – cannot be considered as distributed to a niche market.

All his efforts were informed by an awareness of the delicacy of such operations, and that, in his words, “God’s gift of the press,” if not properly used, could be counterproductive and “result in the death of the sacred letters”.

Manutius’s commitment was impressive and did not go unnoticed. One year after his death, describing the wonderful habits of the Utopia island, Thomas More said that its inhabitants made use only of Aldine editions.

Erasmus of Rotterdam, that most illustrious European humanist – who some years before visited Venice specifically to ask Manutius to print some of his major works, including the impressive collection of Adagia – pointed out that Manutius’s project was far more ambitious than that of the King Ptolemy, founder of the Alexandrian Library.

The latter possessed a library that, no matter how great in size, was still contained within walls. Manutius’s intent was that of “building a library that had no other boundary than the world itself,” – something that implies the ambition and quality of his editorial choices.

The role Manutius assigned to books and education is highly instructive and had a strong influence on Europe and its inhabitants. According to Beatus Rhenanus, one of the humanists closest to Erasmus, the diffusion of the humanistic culture and of the Renaissance spirit all over Europe is due precisely to a Manutius’ conception of publishing.

Despite this indisputable success there failed to emerge a unanimous understanding of the book as a free instrument for communication and education.

The years that followed the death of Aldus Manutius ushered in a long period of fierce political and religious conflict that divided and bloodied Europe.

That largely unconscious freedom that had characterised the first decades of the printed book’s life gave way to repression and censorship.

Europeans grew to learn that with an instrument of such influential potential, never before experienced through previous forms of writing, came great risk.

In the wake of those fierce conflicts, it took more than a century for Europeans to start thinking about the idea of tolerance, developing that concept of freedom of thought and expression which, despite many inherent ideological contradictions, is one of the salient features of European culture.

Mario Infelise -- Eutopia Magazine

translated by Diana Mengo