L’Italia è rientrata nel ristretto gruppo dei paesi creditori verso l’estero. Pur con la pandemia, migliora la nostra posizione creditoria e, dunque, la stabilità finanziaria. Il programma di acquisti della Bce ha favorito le attività di imprese e famiglie.

Attività sull’estero superiori alle passività

Nell’ultimo rapporto sui conti esteri della nostra economica, la Banca d’Italia ha certificato un’importante novità: “Alla fine di settembre 2020 la posizione netta sull’estero dell’Italia era marginalmente creditoria per 3,1 miliardi di euro (0,2 per cento del Pil), dopo oltre 30 anni di continui saldi negativi. Il miglioramento rispetto alla fine di giugno, pari a 31,7 miliardi, è dovuto per oltre tre quarti al surplus di conto corrente”.

Per la prima volta dalla metà degli anni Ottanta l’Italia è ritornata ad avere attività sull’estero superiori alle passività. Un risultato che è frutto di quel sentiero stretto, volto al raggiungimento di una maggiore stabilità finanziaria, che la nostra economia ha imboccato in risposta alla cosiddetta crisi dello spread. Infatti, anche se la posizione debitoria sull’estero dell’Italia non ha mai raggiunto o superato il 35 per cento del Pil fissato dalla Commissione europea come limite per lo squilibrio macroeconomico, la stessa Commissione dovette rilevare che “gli sviluppi verificatisi in Italia nel 2011-2012 dimostrano che anche una posizione patrimoniale netta sull’estero lievemente negativa può rendere un paese vulnerabile a un’inversione dell’afflusso di capitali esteri, con ricadute negative per l’economia”. Questo a conferma della tesi che vede i paesi con una posizione netta sull’estero (Pne) negativa più frequentemente sottoposti alla perdita di fiducia dei mercati, con conseguenti fenomeni di sudden stop dei flussi di capitali, default o ristrutturazione del debito estero e ricorso all’assistenza finanziaria di organismi internazionali (Fmi, Banca Mondiale o Mes).

Per capire come l’economia italiana sia riuscita a ritornare in attivo sull’estero, occorre guardare ai flussi delle partite correnti e del conto capitale cumulati in questi anni. Al netto degli aggiustamenti di valutazione, la variazione della Pne all’interno di un determinato arco temporale è pari al saldo di partite correnti e conto capitale registrato nello stesso periodo.

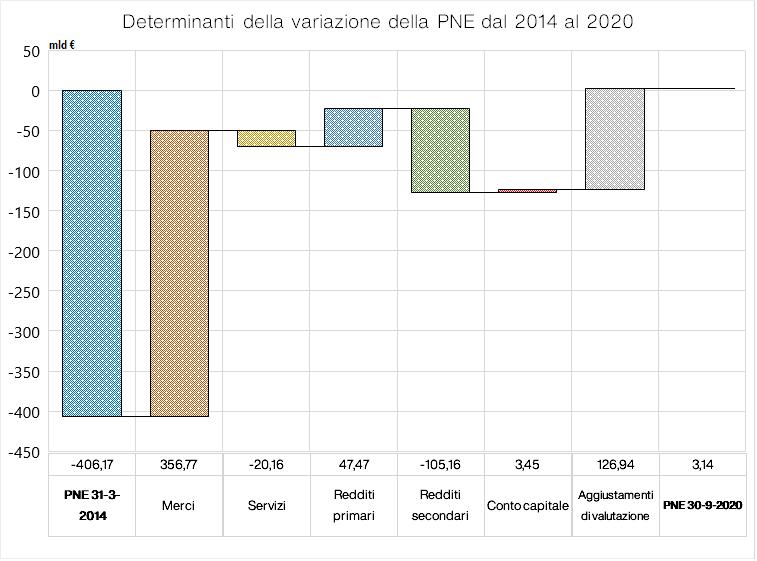

Figura 1 – Determinanti della variazione della posizione patrimoniale netta sull’estero dell’Italia dal 1 trimestre 2014 al 3 trimestre 2020. Dati in miliardi di euro.

Fonte: dati Banca d’Italia

La ripartizione tra settori

Come si nota dalla figura 1, il contributo maggiore al miglioramento della Pne è legato al commercio dei beni. La debole domanda interna di questi anni ha compresso le importazioni portandole ben sotto il livello delle esportazioni. Il conto “Merci” della bilancia dei pagamenti ha registrato dal 2014 al terzo trimestre 2020 un surplus di circa 357 miliardi di euro.

Un altro importante contributo positivo è stato offerto dal conto “Redditi primari”. Per un paese debitore netto e che non ha capacità da centro finanziario globale ci si aspetterebbe che i redditi primari siano negativi, che paghi all’estero più interessi e dividendi rispetto a quelli che riceve. Invece l’Italia, grazie principalmente alla riduzione dei tassi d’interesse conseguente alle politiche espansive della Banca centrale europea, ormai da 4 anni ha raggiunto il surplus in questa voce, che nel 2020 supera i 20 miliardi di euro.

Il conto “Servizi”, dove confluiscono anche i flussi legati al turismo, e i “Redditi secondari”, legati per la gran parte alle rimesse e ai trasferimenti netti alla Ue, hanno invece offerto un contributo negativo. Infine, grazie a circa 127 miliardi di miglioramento nelle valutazioni delle attività estere o diminuzione di valore delle passività, si è raggiunta una posizione patrimoniale netta sull’estero positiva.

Essa però non è ripartita in modo uniforme tra i vari macro-settori dell’economia italiana.

I settori istituzionali pubblici – stato e banca centrale – continuano ad avere una posizione netta abbondantemente negativa. Anche le banche registrano ancora una posizione debitoria, pur essendo notevolmente migliorata rispetto ai circa 260 miliardi del 2014 e ai 400 miliardi raggiunti durante gli anni della crisi dello spread.

Gli altri settori, costituiti da imprese non bancarie e famiglie, dal 2014 ad oggi hanno invece quasi raddoppiato le proprie attività nette sull’estero, che son passate dai 546 miliardi di inizio 2014 ai 1.087 miliardi del terzo trimestre 2020. In questi anni cioè gli italiani hanno continuato ad acquisire attività nette all’estero, favoriti anche dal programma di acquisti della Bce, che ha liberato liquidità aggiuntiva per esser investita in titoli e fondi esteri.

Le ultime previsioni macroeconomiche, pur ipotizzando che lo stimolo fiscale varato per fronteggiare gli effetti della pandemia determini una ripresa della domanda interna e quindi delle importazioni, vedono ancora stabile al 3 per cento del Pil il surplus di partite correnti dell’economia italiana. Le maggiori importazioni dovrebbero esser infatti bilanciate da una analoga dinamica favorevole dell’export, dalla ripresa dei flussi turistici e da un saldo attivo nei trasferimenti con la Ue in conseguenza del Recovery Fund. La posizione creditoria dell’Italia e quindi la sua stabilità finanziaria è destinata a migliorare. Rimangono punti di debolezza legati al settore pubblico, strutturalmente in debito verso l’estero, e alle banche che ancora non hanno recuperato una Pne positiva. Preoccupa di meno la posizione della Banca d’Italia, peggiorata in modo considerevole in questi ultimi 10 anni, ma dovuta esclusivamente al saldo verso l’eurosistema Target2. Un saldo che è conseguenza delle decisioni di politica monetaria della Bce e che, come ripetuto in una serie di occasioni, dovrà essere regolato solo nella remota ipotesi in cui un paese decida di abbandonare la moneta unica.

Anche se sono lontani i valori raggiunti dai grandi paesi manifatturieri (Cina, Germania, Giappone), l’Italia è ritornata nel 2020 a far parte dei paesi creditori verso l’estero, un “club” che fino al trimestre scorso contava solo otto paesi dell’Unione europea e nessuno dei cosiddetti periferici.