Cresce in Italia l’incidenza dei patrimoni e delle eredità, insieme alla loro concentrazione. Per favorire un passaggio generazionale più giusto andrebbe introdotta un’imposta progressiva sui “vantaggi ricevuti”, accompagnata da un’eredità universale.

Più ricchezza e più eredità e sempre più concentrate

Gli italiani sono tra i cittadini più ricchi al mondo: il valore pro capite del nostro patrimonio netto immobiliare e finanziario è pari a circa 143 mila euro. Tuttavia, dalla fine degli anni Ottanta, chi ha meno di 50 anni ha visto la propria ricchezza media diminuire o stagnare. Le nuove generazioni appaiono particolarmente danneggiate, nonostante i rischi connessi alla crescente precarietà del mercato del lavoro. Dal 1995 al 2016, però, la quota di ricchezza netta personale detenuta dall’1 per cento più ricco della popolazione adulta è cresciuta dal 18 al 25 per cento circa. Nello stesso periodo è anche aumentato l’ammontare medio dei lasciti ereditari, da circa 200 a 300mila euro, e quello delle donazioni tra vivi, passato da 100 a 150 mila euro circa).

Benché non certamente l’unica, la ricchezza è una risorsa cruciale per l’uguaglianza di opportunità. Se si crede in tale valore, occorre dunque modificare la situazione attuale. Le vie sono numerose. Accanto a misure di modifica delle regole di distribuzione del valore aggiunto, serve un intervento redistributivo che, con la tassazione, riduca la concentrazione nella parte alta e, con i trasferimenti, assicuri a tutti i giovani una base di ricchezza.

Queste e altre indicazioni sono contenute in un nuovo rapporto del Forum disuguaglianze diversità (ForumDD). Il Forum mira a declinare per l’Italia alcune proposte di politica economica avanzate da Anthony Atkinson nel suo ultimo libro, Inequality what can be done?

Figura 1 – Ricchezza netta media personale per gruppi di età

Fonte: Elaborazioni sui dati dell’Indagine sui bilanci delle famiglie, Banca d’Italia.

Con ricchezza netta si intende la somma di tutti i valori reali e finanziari al netto di tutto l’indebitamento. La variabile della ricchezza netta delle famiglie è allocata agli individui ed è aggiustata stimando le riserve accumulate nei conti pensione e nei fondi assicurativi privati. La ricchezza netta esclude i beni durevoli (per esempio, automobili ed elettrodomestici)

Lo stato attuale della tassazione sui patrimoni ereditati o donati

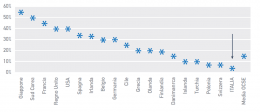

La tassazione dei patrimoni ereditati o ricevuti in dono (non guadagnati) gode in Italia di un regime di forte favore fiscale rispetto a quanto avviene in molti altri paesi. Nonostante l’aumento di ricchezza, le imposte di successione e di donazione, dalla metà degli anni Novanta. sono scese dallo 0,3 allo 0,1 per cento del gettito. Il trasferimento di patrimonio ai figli è oggi soggetto a un’aliquota del 4 per cento solo oltre la soglia di 1 milione di euro, mentre un’eredità di qualsiasi entità ricevuta da uno zio è tassata per intero all’8 per cento. In Francia, ogni figlio ha diritto a un’esenzione di soli 100 mila euro e le aliquote sono progressive fino a una massima del 45 per cento. L’aliquota massima media dei paesi Ocse è del 15 per cento.

Non sorprende, dunque, che anche il Fondo monetario internazionale proponga una modifica dell’imposta di successione e di donazione, che la renda più progressiva e riduca le esenzioni fiscali, allargando la base imponibile.

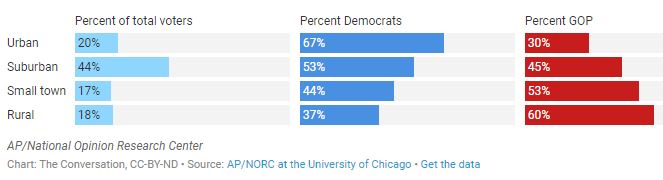

Figura 2 – In Italia diminuiscono gli introiti delle imposte di successione a fronte dell’aumento di rilevanza della ricchezza privata nell’economia

Fonte: World Inequality Data (Wid): rapporto fra ricchezza netta privata e reddito nazionale; Oecd Tax revenue statistics: Introiti delle imposte sulle successioni, eredità e donazioni in rapporto agli introiti fiscali totali. Sono escluse dal computo le imposte catastali, ipotecarie e di registro dovute in caso di eredità di proprietà immobiliari

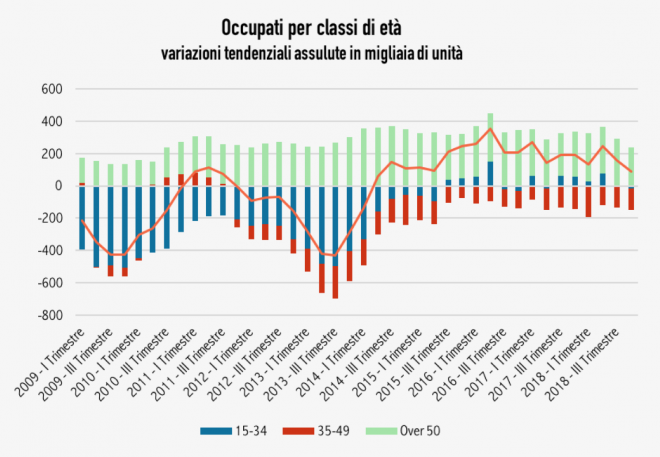

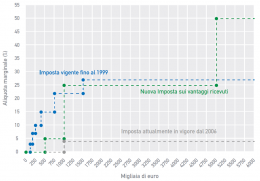

Figura 3 – Percentuale massima del valore tassato (sulla quota ereditata o sull’intero lascito)

Fonte: Elaborazione su dati pubblicati su TaxFoundation. Nel grafico sono stati inclusi solo i paesi con tassazione positiva

Una nuova imposta sui vantaggi ricevuti…

L’imposta sui vantaggi ricevuti, che si applica alla somma dei trasferimenti recepiti nel corso della vita, prevede una soglia di esenzione di 500 mila euro, tre scaglioni e aliquote marginali che vanno dal 5 al 50 per cento, per i trasferimenti cumulati superiori ai 5 milioni di euro. Elimina sia il regime di favore per i familiari diretti sia buona parte delle esenzioni fiscali. I dati catastali andrebbero, ovviamente, aggiornati.

Un’imposta di questo tipo realizzerebbe due principi di buon senso: rendere più equo il regime di tassazione, permettendo a persone che ereditano lo stesso valore patrimoniale di essere soggetti a uguale tassazione, e facendo pagare di più chi eredita di più nel corso della vita.

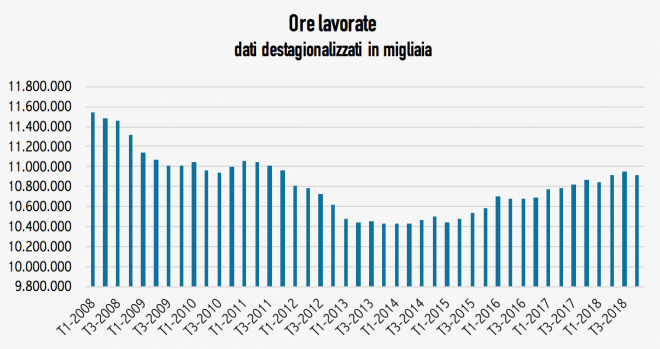

Figura 4 – Un aumento di progressività con la nuova imposta sui vantaggi ricevuti

Le stime preliminari fatte nel rapporto suggeriscono una forte riduzione del numero di persone soggette alla nuova imposta: dagli attuali 110 mila a circa 30 mila.

L’obiettivo principale non è dunque “tassare per tassare”, ma ridurre il regime di sostanziale favore sulle risorse ereditate o ricevute in dono, che hanno pochissime giustificazioni di merito e contribuiscono a divaricare le opportunità.

…e una misura di eredità universale per i 18enni

Le risorse aggiuntive generate dall’imposta sui vantaggi ricevuti, stimate nell’ordine di 1,4-5,2 miliardi di euro (il valore massimo è raggiungibile solo con una riforma del catasto), potrebbero concorrere a istituire un’eredità universale, a favore dei giovani che compiono 18 anni. La proposta, contenuta nell’ultimo libro di Atkinson, è una misura non ancora attuata nel panorama dei paesi Ocse, ma idee simili sono state avanzate anche in UK e Usa. In Italia, una proposta simile è stata presentata di recente da un gruppo di parlamentari del Pd ed era già stata lanciata su questo portale nel 2006 da Valentino Larcinese.

Se si considera una base di 15 mila euro (circa il 10 per cento della ricchezza media) per i circa 590 mila giovani oggi in quella fascia di età, la misura costerebbe circa 8,8 miliardi. Servirebbero, dunque, risorse aggiuntive a quelle provenienti dalla nuova imposta. Potrebbero concorrere una riorganizzazione delle risorse oggi destinate ai giovani (dal bonus cultura, per 240 milioni nel 2019, a una serie di piccoli fondi per le politiche giovanili) e delle agevolazioni fiscali di cui beneficiano oggi le classi di contribuenti più ricchi (il ministero dell’Economia e Finanze certifica un “mancato gettito” da agevolazioni per 55 miliardi annuali). Inoltre, sempre il Mef certifica un ammontare di circa 100 miliardi di imposte evase ogni anno, alle quali si aggiunge il mancato gettito delle imposte sul reddito da lavoro autonomo e sui redditi da capitale relativi ai patrimoni nascosti nei paradisi fiscali (valutato da uno studio della Banca d’Italia in circa 8 miliardi annui). La scelta di destinare i proventi a un’eredità universale per tutte le giovani e i giovani potrebbe aiutare a costruire la pressione necessaria per ottenere risultati, anche marginali, su uno o più di questi fronti.

Il trasferimento è universale: va a tutti i giovani e le giovani, senza prova dei mezzi. È anche incondizionato rispetto alle decisioni di spesa. Questi tratti vanno contro il senso oggi comune. Li difendiamo alla luce delle inevitabili arbitrarietà della selettività e della necessità di rafforzare il senso di comune appartenenza e di accrescere la libertà “sostanziale” dei giovani nel momento del passaggio all’età adulta (libertà di seguire le proprie aspirazioni; di viaggiare; studiare dove si vuole; di tentare, anche in gruppo, un progetto imprenditoriale; di risparmiare). D’altro canto, non condizionalità non implica disinteresse alle scelte. Proponiamo, infatti, di accompagnare alla misura interventi formativi di educazione finanziaria e di guida alle scelte, anche nelle scuole.